A new UNCTAD report says that women are being excluded from better work opportunities, even as their employment participation increases and that of men decreases.

The Trade and Development Report 2017: Beyond Austerity – Towards a Global New Deal attributes intensified job rationing by gender to the increasingly limited availability of good jobs relative to labour supply.

Good jobs are associated with decent work in the formal sector, where earnings are higher, job ladders more accessible and working conditions better regulated. The scarcity of good jobs is driven by the prevailing global policy environment, along with the forces of structural and technological change.

According to UNCTAD, excluding women from good jobs deepens overall inequality by lowering the share of labour in national income, with negative consequences for aggregate demand and, ultimately, growth.

Yet increasing women’s employment is not a straightforward pathway to more inclusive growth and development, the report emphasizes. “There is much more to do to reach gender equality in employment than to increase the participation of women in markets and boardrooms,” said UNCTAD Secretary-General Mukhisa Kituyi.

The report concludes that facilitating women’s access to decent employment – especially through social infrastructure investments that better enable women to combine paid work and any responsibilities for care – are crucial. Pairing such efforts with demand-side interventions, including through more expansive fiscal stances, can make growth more inclusive for women and increase the demand for labour, thereby also improving economic prospects for men.

Most importantly for the long term – given the employment challenges associated with structural and technological change, and women’s primary responsibility for care work – UNCTAD recommends transforming unpaid and paid care activities into decent work, and that this should become an integral part of strategies aimed at building more inclusive economies.

Including women, excluding men?

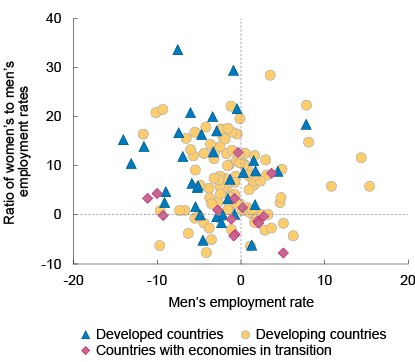

Against the backdrop of boom and bust cycles, austerity and mobile capital, and with women’s employment rates rising, as they are in most countries, and men’s employment rates falling, achieving greater gender equality in employment can become more difficult. This is a phenomenon that is not yet widely discussed and, although its strongest manifestations are in more advanced economies, it is becoming a feature of job markets worldwide (see figure).

Ratio of women’s to men’s employment rates versus men’s employment rate, 1991−2014 (Percentage)

Source: UNCTAD, 2017, Trade and Development Report 2017: Beyond Austerity – Towards a Global New Deal (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.17.II.D.5, New York and Geneva).

Note: The top left quadrant shows that the ratio of women’s to men’s employment rates increases as men’s employment rate decreases.

Between the early 1990s and 2014, among the 80 per cent of developed countries in which men’s employment rates decreased, the average decrease was by 5.3 percentage points. At the same time in these countries, women’s employment rates increased by an average of 2.3 percentage points.

There are greater variances among developing countries yet more than half display patterns of declining employment rates for men and rising rates for women. Among these countries, men’s employment rates decreased by an average of 2.7 percentage points and women’s employment rates increased by 6.3 percentage points.

Industrialization failures costlier for women than men

The hollowing out of traditional factory jobs and manufacturing communities has been a highly visible feature of growing inequality in developed countries, and affects middle-aged men in the working classes in particular.

Yet the number of jobs in the industrial sector is also declining in many developing countries that are experiencing premature deindustrialization and stalled industrialization, and the negative impact is much greater on women’s employment in industry than on men’s. In developing countries in

1991–2014, the decline in the share of industrial employment in total employment was by an average of 7.5 per cent for men, compared with an average of 39 per cent for women.

Increasing the physical capital used in industrial production is particularly costly for women. With the increase in capital intensity associated with automation, it seems unlikely that a technological revolution in the South will improve gender equality in the near future.

Press Release

For use of information media - Not an official record

UNCTAD/PRESS/PR/2017/030 TDR-Austerity generating gender exclusion, says United Nations

Geneva, Switzerland, 14 September 2017