A strong and vibrant international enabling environment and the biggest coordinated investment push in history will be essential if the new, ambitious, universal and multidimensional 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is to be achieved.

Kick-starting growth and tackling the factors holding down global trade growth – one of the most urgent issues affecting the world economy today – will be addressed by decision makers in public policy, international organizations, civil society and the private sector at the UNCTAD four-yearly ministerial conference taking place in Nairobi on 17–22 July.

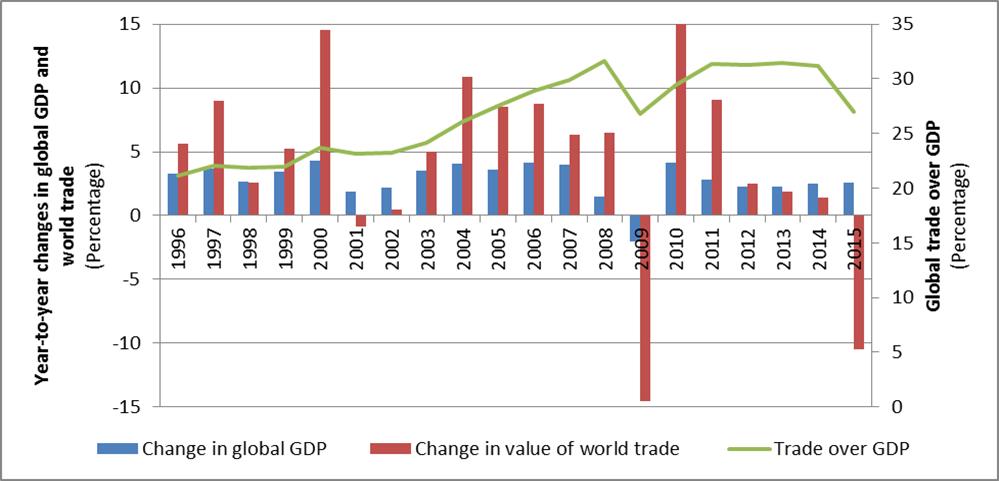

Global trade continues to be affected by sluggish global demand, reduced commodity prices and persistent political turmoil in various parts of the world. In 2015, global merchandise trade amounted to about $16.5 trillion (down from almost $19 trillion in 2014) and trade in services, to about $4.9 trillion (down from about $5.2 trillion in 2014). Since international trade has been an enabler of economic growth, technological upgrading and rising productivity, an enduring period of declining trade and weakened economic integration could reduce the benefits to be reaped from globalization and pose serious constraints on developing countries in meeting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Current trade patterns depart in several ways from those of the past:

- World trade has now entered its fifth year of stagnation. Such a long period of apathy for international trade is unprecedented in recent times. As of 2015, the value of world trade is at about the same level as in 2008.

- Developing countries are no longer the engine of trade growth that they were in the past. While developing countries’ trade performance has almost always outperformed that of developed countries in the last two decades, since 2013 trade performance of developing countries has been relatively weaker than that of developed countries.

- Recent years have seen a departure from the close relationship between international trade and economic growth. In particular, while international trade has historically grown at a substantially faster rate than global output, since 2013 it has been growing at a slower pace. In other words, the slowdown in world trade has not been due to generally lower economic growth alone but international trade has also been much less responsive to global output growth (see figure).

From a policymaking perspective, these changing patterns in international trade imply that developing countries seeking to benefit from it should adapt their development strategies. Decisive government responses are particularly important as many of the factors behind the global trade slowdown are likely to be long lasting and related to structural shifts. In particular, while commodity price cycles and delayed investment decisions are surely contributing to more short-term trade patterns, the economic rebalancing of some East-Asian economies from more export-driven to more consumer-driven growth paths would indicate more long-lasting structural shifts. Moreover, changes in trade patterns are also due to the evolving structure of global value chains. Although these have greatly contributed to the expansion of trade in the past, their contribution to trade growth is now thought to have largely stabilized and, in some cases, gone into reverse. The cost-reducing effects on trade from information and communications technologies are likely to have already been realized and any further substantial gains could be limited. Moreover, reduction in other trade costs and regulatory harmonization has not progressed fast enough to provide new incentives to further “de-localization” of production processes.

There are several areas where policy intervention could garner the largest developmental impact of trade. For instance, support to technological upgrading by firms could enhance their competitiveness in economic sectors where world demand is more likely to increase, such as services. Government policies could also facilitate the integration into international markets of more dynamic segments of the economy. In this context, policies aimed at reducing transactions costs for innovative small and medium-sized enterprises may result in new trade opportunities. Perhaps most importantly, Governments should also further pursue regional integration among developing countries. Broadening the scope of regional cooperation initiatives is likely to improve trade opportunities especially for firms in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In this respect, economic opportunities related to supply chains remain rather underdeveloped in many regions, and there is much room for firms in developing countries to benefit from such opportunities.

Finally, Governments should avoid taking the trade slowdown as an incentive to recur to protectionism or other beggar-thy-neighbour policies. While the use of traditional trade policies such as tariff barriers has not changed much in the last few years, the use of non-tariff measures has been increasing. Using these measures should be limited to the need to respond to public policy concerns such as health, safety and the environment or serve development and social goals while minimizing trade distortionary effects.

Although uncertainty surrounding the evolution of world trade will remain in coming years, it is most likely that the factors and the policies that helped fuel trade growth in the past have exhausted most of their effect. For international integration to resume, Governments need to advance a forward-looking trade agenda. At the fourteenth session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development – UNCTAD 14, policymakers will focus their discussions on the key elements of such an agenda with the aim of reigniting global trade in support of inclusive economic growth and poverty eradication.

Changes in the trade-to-gross domestic product relationship: Is the global economy entering a de-globalization period?

Source: UNCTAD calculations based on UNCTADStat data.

Abbreviation: GDP, gross domestic product.

Note: Data for 2015 are preliminary.