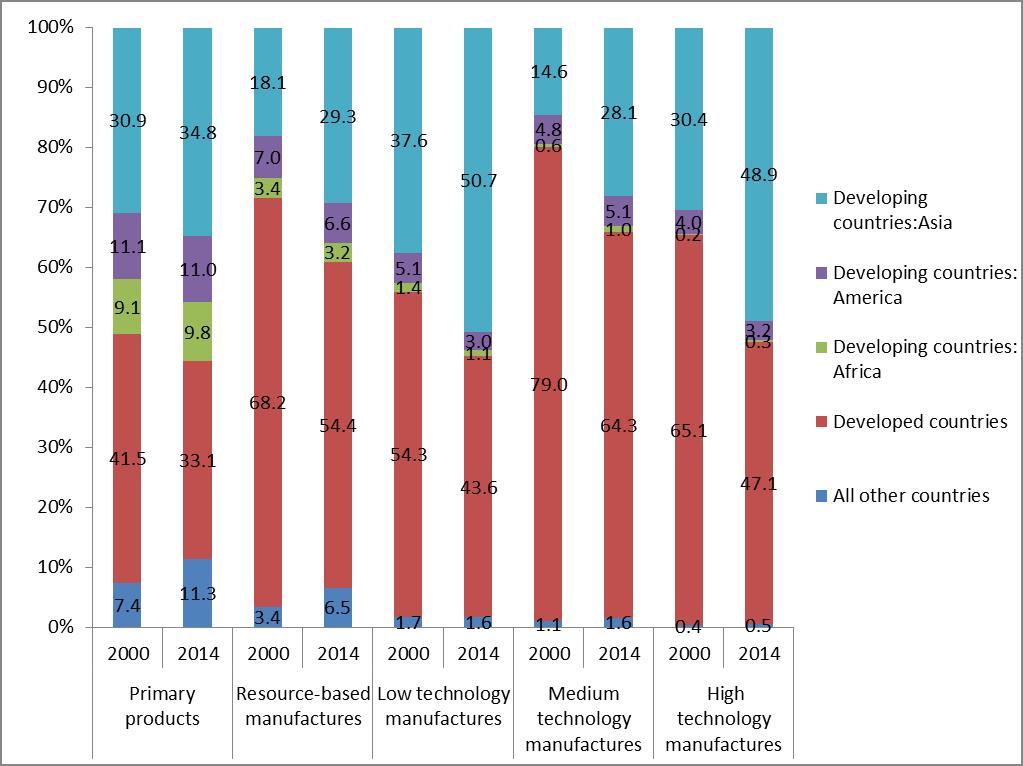

Although developing countries as a whole accounted for 52 per cent of global exports of high technology products in 2014 – an 18 percentage point rise since 2000 – African countries are lagging behind, representing just 0.3 per cent of this total, the UNCTAD Technology and Innovation Report 20151 has found (see figure). The report, subtitled Fostering Innovation Policies for Industrial Development, examines how Africa’s Governments can better implement science, technology and innovation policies, and coordinate them with industrial policies and industrial development plans.

The report found that, mainly because of difficulties in coordinating those two policy frameworks, even African countries that spend more on research and development as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) do not manage to export more high- and medium-technology products.

To shed light on this picture, the report provides in depth analyses of industrial and science, technology and innovation policies in Ethiopia, Nigeria and the United Republic of Tanzania, along with regional trends and initiatives in policies in other African countries. The report shows that patterns of policy conceptualization, design, planning and implementation are critical to the success of companies and hold the key to making technology work for business.

According to UNCTAD, recent studies have shown that it is not enough to just have a policy emphasis on technology-led growth. Instead, the success of policies depends on how policy processes work to facilitate collaboration and cooperation between policy agencies, companies, businesses and research. Moreover, policymakers need to formulate industrial policies not as a standalone framework but in coherence with other policies, for example innovation policy.

As subjects of the study, the Ethiopia, Nigeria and the United Republic of Tanzania were chosen for their differing economic profiles: while Nigeria is an oil-rich developing country, Ethiopia is a least developed country with a resource-concentration in agriculture, mainly coffee. These countries are juxtaposed with the United Republic of Tanzania, which has a mix of resource-based activities and other sectors. Thus, each country serves to illustrate a developmental challenge in the realm of coordination of industrial and innovation policies for developmental outcomes.

Each country also has national vision documents, new industrial development strategies and science, technology and innovation policies that embody the aspiration of their Governments to transform the nations into middle-income economies within the next two to three decades.

In addition, all three countries had relatively impressive GDP growth rates over the past decade, if not longer, and increased research and development expenditure as a percentage of GDP in the 2000s. Despite this, they have faced difficulties in focusing those investments into greater technological learning, particularly in firms, as demonstrated by the lack of medium- and higher-technology products in their exports.

Almost all countries in Africa, including the three countries that were studied, and more generally in the developing world, are currently at a developmental stage where industrial development through technological change should be a central, if not the most important, priority. Not only is there a policy transition in that direction, the field surveys showed the extensive degree of political commitment to enacting elaborate industrial policy frameworks and revising science, technology and innovation policies towards innovation.

Notably, the report finds that there are overlaps between industrial and innovation policies. While industrial policy aims at facilitating structural transformation by promoting certain economic activities, sectors and technologies with development potential, innovation policy aims at promoting technological learning and adaptation. Industrial policy has an extensive framework that also includes aspects of innovation policy, as structural transformations are possible when they facilitate capabilities for knowledge accumulation and transfer within and across firms and sectors. These two policies often use similar incentives and instruments.

The report highlights six points on innovation and industrial development that are highly relevant for African countries:

• Innovation policies are quite new to African countries and thus often not well implemented

• Innovation systems in African suffer from many shortcomings, many of which inhibit their effectiveness

• Industrial policies in many African countries followed in the past did not have much emphasis on promoting technological learning

• Even if industrial development policies had a technological change focus they were not properly coordinated with science, technology and innovation policies

• Most firms, which are family-owned and operate on a small scale, often face financial constraints and capacity problems in acquiring new technologies; moreover, lack of skilled human resources, “brain drain” effects and governance problems in technology transfer hinder innovation in these economies

• To stimulate sustainable industrial development in the region, firms need a more coherent policy environment.

The report also finds that existing policies do not always correspond to the reality of the situation on the ground. The private sector in the African region (particularly in sub-Saharan Africa) is in dire need of greater support and, therefore, taking on board on-the-ground realities of businesses is critical, the report argues. Policymakers in developing countries need to establish an inclusive policy process that assembles stakeholders from different sectors of the economy, including ministries, public sector institutions, private sector companies, universities and research institutes. This would allow incentives for local firms, such as research and development grants and loans, tax credits and governmental procurement, to be relevant to local needs and effective as incentive tools.

UNCTAD’s Technology and Innovation Report 2015: It can be done

Despite identifying significant science, technology and innovation policy gaps in Africa, the report found positive examples of collaboration which support its recommendations.

In the United Republic of Tanzania, for example, there is a family-owned company that began producing 200 kilograms per year of dried fruits and vegetables, such as dried mango, pineapple and banana. With the coordinated assistance of various partners, though, it has expanded annual output to 5–7 tons. Relying on cost-efficient sun-drying methods since it began trading in 2002, the firm developed its drying facility in phases. First, the company received support in the form of machinery and know-how from a German partner; then the Department of Chemical and Process Engineering of the University of Dar-es-Salaam and the Tanzania Traditional Energy Development Organization offered their expertise. The firm has also received support from the Government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. Later expansion plans include the installation of an electric dryer.

The report also underscores a positive case in Ethiopia, with respect to institution-building, where the Food, Beverages and Pharmaceuticals Industry Development Institute was recently founded by the Ministry of Industry. The institute acts as a one-stop shop to assist the food processing and the pharmaceuticals sectors, and it has proved critical to boosting the capacity of the two sectors, particularly when it comes to upgrading production facilities. It also provides research, laboratory and testing services. The initiative is a first of its kind in Ethiopia, and its future success will largely depend on infrastructure and manpower. When the report was being written, the agency was limited by funding and weaknesses in human skills and infrastructure that policymakers have acknowledged and which were expected to be addressed soon.

Distribution of world exports, by technology intensity and development status in 2000 and 2014

(Percentage)

Source: UNCTAD.

Note: The 2014 figures are estimates.

Report: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tir2015_en.pdf

Overview: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tir2015overview_en.pdf